Without a doubt, though, the best known person of African descent in the Texas Revolution was William B. Travis’ slave named Joe. Travis brought Joe with him when he travelled to Béxar. Joe shared the hardship of the siege and even took part in the defense of the Alamo on the morning of March 6, 1836 only leaving the walls after Travis was killed. Having survived the battle, Joe was sent to Gonzales to spread the word of what had happened. Starved for news of the battle, Joe was brought before officials of the Texas government to tell them what he had witnessed. In fact, Joe’s account of the Alamo became the basis of the traditional tale of the battle. -Dr. R. Bruce Winders, Former Alamo Director of History and Curator

African Americans in Mexican Texas

Joe’s Account of the Battle of the Alamo

Sunday, March 20, 1836

This morning Messrs. Zavalla, Ruis and Navarro arrived. The cabinet are now all here, except Hardiman. The servant of the late lamented Travis, Joe, a black boy of about twenty-one or twenty-two years of age is now here. He was in the Alamo when the fatal attack was made. He is the only male, of all who were in the fort, who escaped death, and he, according to his own account, escaped narrowly. I heard him interrogated in the presence of the cabinet and others. He related the affair with much modesty, apparent candor, and remarkably distinctly for one of his class. The following is, as near as I can recollect, the substance of it:

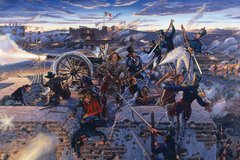

The garrison was much exhausted by incessant watching and hard labor. They had all worked until a late hour on Saturday night, and when the attack was made sentinels and all were asleep, except one man, Capt. -----------, who gave the alarm. There were three picket guards without the fort, but they, too, it is supposed, were asleep, and were run upon and bayoneted, for they gave no alarm. Joe was sleeping in the room with his master when the alarm was given. Travis sprang up, seized his rifle and sword, and called to Joe to follow him. Joe took his gun and followed.

Travis ran across the Alamo and mounted the wall, and called out to his men, "Come on boys, the Mexicans are upon us, and we'll give them Hell." He discharged his gun; so did Joe. In an instant Travis was shot down. He fell within the wall, on the sloping ground, and sat up. The enemy twice applied their scaling ladders to the walls, and were twice beaten back. But this Joe did not well understand, for when his master fell he ran and ensconced himself in a house, from which he says he fired on them several times, after they got in. On the third attempt they succeeded in mounting the walls, and then poured over like sheep. The battle became a melee. Every man fought for his own hand, as best he might, with butts of guns, pistols, knives, etc.

As Travis sat wounded on the ground General Mora, who was passing him, made a blow at him with his sword, which Travis struck up, and ran assailant through the body, and both died on the same spot. This was poor Travis' last effort. The handful of Americans retreated to such covers as they had, and continued the battle until one [only?] one was left, a little, weakly man named Warner, who asked for quarter. He was spared by the soldiery, but on being conducted to Santa Anna, he ordered him to be shot, and it was done. Bowie is said to have fired through the door of his room, from his sick bed. He was found dead and mutilated where he lay. Crockett and a few of his friends were found together, with twenty-four of the enemy dead around them. The negroes, for there were several negroes and women in the fort, were spared. Only one woman was killed, and Joe supposes she was shot accidentally, while attempting to cross the Alamo. She was found lying between two guns.

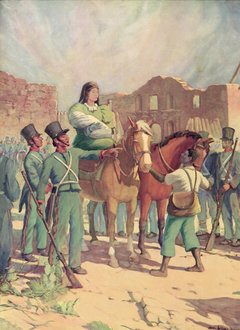

The officers came around, after the massacre, and called out to know if there were any negroes there. Joe stepped out and said, "Yes, here is one." Immediately, two soldiers attempted to kill him, one by discharging his piece at him, the other with a thrust of the bayonet. Only one buckshot took effect in his side, not dangerously, and the point of the bayonet scratched him on the other. He was saved by Capt. Baragan.

Besides the negroes, there were in the fort several Mexican women, among them the wife of a Dr. and her sister, Miss Navarro, who were spared and restored to their father, D. Angel Navarro of Bejar. Mrs. Dickenson, wife of Lieut. Dickenson, and child, were also spared, and have been sent back into Texas. After the fight was over, the Mexicans were formed in hollow square, and Santa Anna addressed them in a very animated manner. They filled the air with shouts. Joe describes him as a slender man, rather tall, dressed very plainly--somewhat "like a Methodist preacher," to use the negro's own words.

Joe was taken into Bejar, and detained several days; was shown a grand review of the army after the battle, which he was told, or supposes, was 8,000 strong. Those acquainted with the ground on which he says they formed think not more than half that number could form there.

Santa Anna questioned Joe about Texas, and the state of its army. Asked if there were many soldiers from the United States in the army, and if more were Joe with Mrs. Dickinson and daughter expected, and said he had men enough to march to the city of Washington. The American dead were collected in a pile and burnt.

William Fairfax Gray, Diary of Col. Wm. F. Gray (Houston: Fletcher Young Publishing Co., 1965), 136-141.

NOTE: One legend tells of Joe returning to Alabama after his escape to tell the Travis family of his master's death at the Alamo. He is also said to be buried in an unmarked grave in Brewton, Alabama. Joe was last reported in Austin in 1875 before fading from history.