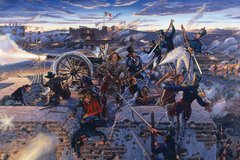

Former Mission San Antonio de Valero had served as quarters for Spanish and Mexican soldiers for almost thirty years prior to the outbreak of the Texas Revolution. Béxar’s role as a garrison town was one factor that drew Cos there. Upon the approach of the Austin’s Federal Army of Texas, Cos began fortifying the town, throwing up barricades across streets leading to the main plaza in front of San Fernando Church. Across the river at the Alamo, Cos’ engineers constructed artillery platforms at various points and built an earthwork to protect the compound’s main gate. They even placed at least one cannon on a platform at the east end of the church. The compound served as a cuartel or barracks for some of Cos’ units defending the town. The Alamo was included in Cos’ surrender of the town and its public property, which allowed the rebels to occupy the fortified compound as their barracks.

Returning to the logical progression of revolutions, governments have an obligation to retake important locations captured by rebels. One reason is that rebels must be punished for their disloyalty. Another reason is that the government must show that it will not let the rebels’ gains stand. Having lost both Goliad and Béxar, the Mexican Army made plans to recapture these two important places. General José Urrea led one column to Goliad while Santa Anna personally led another to Béxar. This strategy initially proved very effective in returning control of Texas to the Mexican government.

As mentioned earlier, the traditional assumption is that the Alamo, located on the outskirts of Béxar, was a worthless mission the in the middle of nowhere and therefore it was pointless and even foolish for the Texans to try to defend it. Although Sam Houston believed the town should be abandoned, other influential Texans disagreed. On January 17, 1836, Houston had written Governor Henry Smith that he had “ordered the fortifications in the town of Bexar to be demolished, and if you should think well of it [italics added for emphasis], I will remove all the cannon and other munitions of war to Gonzales and Copano, blow up the Alamo, and abandon the place, . . .”[1] Houston’s argued that it would be “impossible to keep up the Station with volunteers” against the Mexican Army when it returned. He also contended that a site behind the frontier and closer to the line of supply would be better for gathering and training recruits.

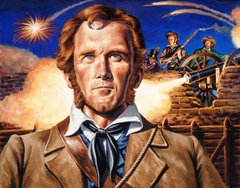

But neither the governor nor the members of the General Council “thought well” of Houston’s suggestion and instead ordered the town reinforced. Bowie, who had already been sent to Béxar by Houston, saw the situation differently once he arrived. Writing Smith on February 2, 1836, Bowie contended that the “salvation of Texas depends in great measure in keeping Bejar out of the hands of the enemy. It serves as the picquet guard and if it were in the possession of Santa Anna there is no strong hold from which to repell him in his march towards the Sabine.” He then added a line which was to become famous, “Colonel [James C.] Neill and myself have come to the solemn resolution that we will rather die in these ditches than give up this post to the enemy.”[2]

Ten days later, William B. Travis, who had been sent to Béxar by the governor after receiving Bowie’s letter, reinforced the importance of holding the town, telling Smith, “This being the Frontier Post nearest the Rio Grande, will be the first to be attacked — We are illy prepared for their reception, as we have no more than 150 men here and they in a very discouraged state — Yet we are determined to sustain it as long as there is a man left; because we consider death preferable to disgrace, which would be the result of giving up a Post which has been so dearly won, and thus opening the door for the invaders to enter the sacred Territory of the colonies.”[3] Travis wrote Smith again the next day, February 13, to reiterate the need to defend Béxar, saying “it is more important to occupy this Post than I imagined when I last saw you — It is the key to Texas from the Interior without a footing here the enemy can do nothing against the colonies now that our coast is guarded by armed vessels.”[4] Even Santa Anna realized the importance of the town, writing after the revolution that “Béxar was held by the enemy and it was necessary to open the door to our future operations by taking it.”[5] The statements of Bowie, Travis, and Santa Anna refute the notion of Béxar, and by extension the Alamo, as being a place of no value.

While the 1835 Battle of Béxar receded from historical memory, the 1836 Battle of the Alamo took center stage in the Texas Revolution. Governor Smith, James C. Neill, James Bowie, William B. Travis, and others never believed that the small force at the Alamo could hold back the Mexican Army. The Alamo’s defense ultimately relied on Texans returning to Béxar to confront any new threat. Travis’ famous letter of February 24, 1836, addressed to “The People of Texas and All Americans In The World,” announced the need for Texans to return to Béxar. This gives meaning to his words, “I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism, & every thing dear to the American character, to come to our aid, with all dispatch.”[6] His call set events in motion, but time and distance were not on his side. Thirty-two residents of Gonzales, who lived only 75 miles away, arrived. Additional volunteers who had come from settlements further to the east were still gathering at Gonzales a week later, yet unaware that the Alamo had fallen. Houston found nearly 350 volunteers waiting there when he rode into town on March 11, 1836, fresh from the convention on Washington on the Brazos River, where the new government had reconfirmed his command of the army. Shortly afterwards news of the Alamo’s fate reached Gonzales, sending both Houston’s newly acquired army and panicked civilians streaming eastward.

The Alamo now took on a new symbolic meaning. The loss of Béxar and its garrison electrified the Texans. Spoiling for a fight, they finally had their chance for revenge on April 21, 1836, on the bank of San Jacinto River. Officers reminded their men why they were fighting. They did not need to be told, though. They knew the outcome would be “Victory or Death.” Furthermore, they had known many of the men slain at Béxar either personally or by reputation. It is likely that the cry “Remember the Alamo!” came naturally to them. “Remember the Alamo?” How could they forget the loss of such an important place and the death of relatives, friends, and companions in arms who gave their lives to defend it?[7]